Editors note: This is the second part of a two part series, to learn about the causes behind storm water pollution see part 1.

Infrastructure improvements are on the way to address the monstrous amounts of polluted stormwater draining onto beaches, but it could take decades until the effects of these projects build a groundswell of environmental change.

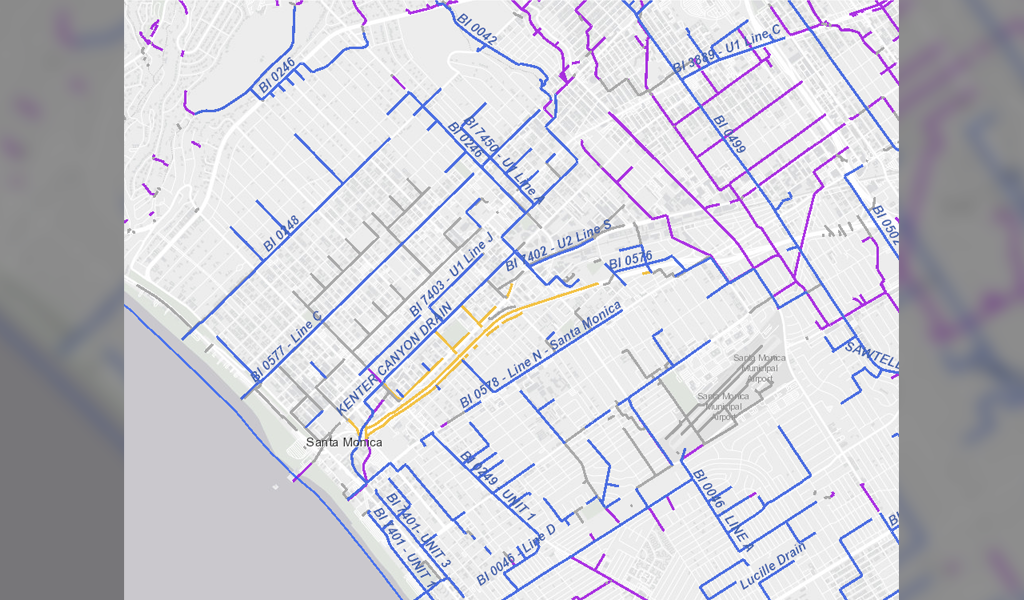

Fortunately, Santa Monica is at the vanguard of the stormwater mitigation movement. Unfortunately, it’s also at the forefront of the stormwater pollution problem with the Pico-Kenter storm drain, Pier storm drain and several others dumping millions of gallons of runoff into the ocean each year.

This is, almost, by no fault of the City itself. Pollution generated in Santa Monica represents only a fraction of the toxins washed into the ocean through the stormdrain system that channels runoff from thousands of miles inland.

The entire Los Angeles County Flood Control District encompasses 2,700 square miles within six major watersheds. In the Santa Monica Bay watershed alone, 30 billion gallons of polluted runoff are released annually.

When rain falls it accumulates trash, chemicals, bacteria, hardmetals and fertilizers as it flows through the County towards the ocean, which, in the instance of significant rain events, can cause devastating environmental consequences and risks to human health.

Tides of change are arriving soon, at least on a local level, with Santa Monica’s $96 million Sustainable Water Infrastructure Project (SWIP) slated for completion in August 2022.

While SWIP might not be the sexiest sounding name, the initiative will generate community benefits that range from desirable to downright thrilling. These include cleaner local beaches, water self-sufficiency, replenishment of groundwater resources and a potential reputation for leading a stormwater recycling revolution.

The project consists of three elements: upgrades to the existing SMURFF water treatment plant, construction of two new stormwater harvesting tanks and the creation of a state-of-the-art sewage and stormwater recycling facility.

The system will work by capturing run-off at the Pico-Kenter storm drain in harvesting tanks, separating out trash, and sending the water for treatment at the SMURRF plant and the new SWIP treatment plant. Recycled water can be utilized by the City and local households, and can replenish Santa Monica’s valuable groundwater wells.

“This project will take away up to 1.5 million gallons of water in any given 24 hour rain event, and by not releasing that water, all of the pollution contained in it will also be captured and eliminated,” said Selim Eren, Santa Monica civil engineer.

The new treatment plant is being constructed under the Civic Center parking lot. It is the first underground facility in California that will convert municipal wastewater, stormwater and dry weather urban runoff into potable water.

“It’s definitely very innovative and unique in the United States, so I think we’ll set a great example for years to come,” said Eren.

Although the near $100 million price tag is hefty, the project has significant economic benefits.

Currently, Santa Monica pays to import around 30 percent of its water supply and pays for the City’s wastewater to be treated at the Hyperion plant in El Segundo. SWIP will help Santa Monica become water self-sufficient, decrease import and processing costs and create a drought-resistant water source.

“Having sustainable, long-term, self-sufficient, locally-produced water resources has long been a goal of City Council dating back to 2010, when staff were first directed to look into ways to increase local production,” said Eren.

The decrease in polluted run-off rushing onto local beaches will be a primary environmental benefit of SWIP. However, there will also be broader benefits that come from stopping the energy-intensive import of water and serving as a model for other municipalities to build similar facilities.

At the County level the state of stormwater mitigation efforts is more stark.

According to Dan Lafferty, deputy director for water resources at L.A.

County Department of Public Works, it would take $20 billion of investment in mitigation projects over 20 years to bring the County’s storm drain system into compliance with the standards established by the EPA’s Clean Water Act.

“The reason there’s the 20 year time period is that these projects tend to be very large, siting them is a challenge and you still have to go through the design and the regulatory process to get approval to build,” said Lafferty. “On average, these projects take anywhere from three to seven years from idea to completion.”

Los Angeles County needs a lot of stormwater capture and processing facilities as around 95 percent of stormwater drains into the ocean. This occurs for several reasons.

L.A. is highly developed and covered in impervious surfaces such as concrete and asphalt. The natural geology of the area also makes it difficult to filter runoff into underground aquifers. The way the flood control system was designed starting in 1915 focused on centralizing all flows towards the ocean, limiting the opportunity for upstream diversion.

Collectively, this means that even when the SWIP project is complete in 2022, millions of gallons of runoff from the County will still flow out of the Pico-Kenter storm drain in the rainy season.

Recognizing the dire need for stormwater mitigation efforts, L.A. County voters passed a parcel tax called Measure W in 2018, which provides dedicated funding for these infrastructure projects. SWIP received $20 million in Measure W funding, while the remaining $76 million is funded by special low-interest financing from the state.

Similar infrastructure developments are underway across the County, with municipal projects likely to come online in the next few years and larger DPW run regional projects working on a longer timeline.

These projects are promising, but according to Lafferty, Measure W only provides about 20 percent of the funding needed to bring the storm drain system into EPA compliance.

In addition to these facilities, the Department of Public Works is looking into ways to divert water runoff into the existing sewage system for processing.

“Significant urban water conservation efforts—all of the low flow toilets and low flow shower heads we’ve been involved in—actually resulted in a 25 percent drop in the amount of sewage being delivered to sewer treatment plants,” said Lafferty. “That creates an opportunity for us as a stormwater agency to make use of that capacity.”

Currently, DPW diverts dry weather runoff into the sewer system using around 40 diversions located by the coast. Dry weather season is typically from May to October and run-off flows are generated by things like irrigation, street sweeping and carwashes.

Several dry water diversions are located in Santa Monica, including the existing SMURFF facility and diversions at the Pier, Montana Ave and Wilshire Blvd.

The system works by holding back dry weather runoff using dams inside the storm drain pipelines. The runoff can then be collected and pumped over to the sewer system. The dams are short or deflatable, so that stormwater can flow through and not get backed up if there is a rain event.

“In the summer, if you look at the history of the Heal the Bay beach report cards, you can see significant improvement in those scores over time and the bulk of that improvement is really a result of the effort to build these dry weather diversions,” said Lafferty.

DPW is now seeking to adapt the system so that diversions can be used during wet weather events. According to Lafferty, this concept has great potential, but will take many years to bring to fruition.

“That pilot project is probably about five years away, but it has a lot of promise based on the analysis we’ve done so far,” said Lafferty, adding that just the process of building the dry water diversions took 15 to 20 years.

All of these initiatives—water conservation, flow diversion, stormwater tanks and recycling facilities—are steps in the right direction. But, due to both the time they take to construct and the billions of gallons needing diversion, they are currently drops in the bucket for addressing Los Angeles’s stormwater pollution problem.

With climate change accelerating, drought on the horizon, and the ocean’s health deteriorating, the need to capture and process polluted stormwater is only growing more urgent.

Clara@smdp.com