A massive new infrastructure project is set to come online in Santa Monica this fall — whether you notice it or not. City of Santa Monica Public Works Department staff hope you won’t.

“That’s actually our motto: Out of sight, out of mind,” Water Resources Manager Sunny Wang said during a recent tour of the project site. “If somebody notices, that means we’ve got a problem.” Wang, with project engineers Jason Hoang and Selim Eren, spent an hour walking through the construction site detailing the project on a sunny afternoon in early February.

When it’s completed, which City officials anticipate will happen in September 2022, the site near the intersection of Pico Boulevard and Main Street will look like a newly repaved parking lot with concrete planters and a bike lane linking Pico Boulevard to Civic Center Drive. The site also includes a new sports field that has already opened across 4th Street from Samohi and the Early Childhood Education Center.

But 45 feet below the surface — underneath a three-foot-thick slab of concrete — the $95 million Sustainable Water Infrastructure Project, nicknamed SWIP, will be converting millions of gallons of stormwater and sewage into purified water to be used for irrigation, pumped into dual-piped buildings and injected into the groundwater basin to prepare it for purification into potable water.

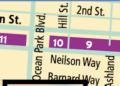

The project, which broke ground in January 2020, will draw raw sewage from the Ocean Ave Sanitary Sewer — to the tune of about 1.5 million gallons per day, or a little under 10 percent of the daily sewage output in the city of Santa Monica. It will also collect stormwater runoff otherwise destined for the Pico-Kenter storm drain. Project engineers anticipate SWIP will improve water quality in the Santa Monica Bay, which is always adversely affected on rainy days, by collecting and treating up to 85 percent of the urban runoff that otherwise flows directly from Los Angeles’ street corners onto Santa Monica Beach via Pico-Kenter.

The blending of the two water sources will help dilute the sludgy urban runoff to make it easier to treat, Wang detailed. The plant includes a 1.5-million-gallon basin to collect stormwater runoff, allowing a mix of up to 30 percent stormwater and 70 percent sewage at any time.

“We’re actually using wastewater to dilute down stormwater,” Wang said. “Stormwater, it’s actually harder to treat than wastewater because of the heavy metals, the stuff that people put on the street and that gets flushed down the streets. There’s a lot of stuff that’s really difficult to remove and treat.”

Water treatment at SWIP involves a six-step process that begins with the removal of solids and includes cartridge filtration, reverse osmosis, ultraviolet light treatment and chlorine contact. The steps help to remove not only solid waste but pharmaceuticals, personal care products like shampoo and conditioner, and viruses and bacteria.

“We’re required to provide 12-log removal of virus,” Wang described. “One-log is 90 percent. Two-log is 99 percent. So, you can imagine what 12-log is: 99.9999 — 12 nines — removal of viruses. When you think about what is actually left in that water, it’s not much.”

According to Wang, the Hyperion water treatment plant that filters much of LA’s sewage and releases it into the ocean simply filters out solid waste, processes the water through sedimentation (allowing it to settle and remove sediment) and then releases it into the ocean. SWIP does much, much more. The resulting treated water far exceeds the standards for drinking water put forth by the State of California, but it won’t be flowing out of your kitchen faucet — at least not yet.

“To make it into drinking water quality, it goes through the cartridge filters, the reverse osmosis, and then the UVA mass oxidation and the chlorine disinfection, so, several more steps to get it to that water quality,” Wang said. “Those are things you typically don’t see at a wastewater treatment plant — some of these technologies you typically don’t even see at a drinking water treatment plant. So, it really depends on what’s in your source water, what you’re trying to remove.” Wang said the treatment process included multiple redundancies in a six to seven-step process, whereas many treatment plants use a four-step process.

Currently, treated sewer water cannot be converted into drinking water without first entering a groundwater basin, but City engineers said they expect state regulations may change in coming years as more plants like SWIP come online. If so, Santa Monica is poised to add recycled water into the drinking water mix.

“I think all we need is a booster pump and a pipeline to connect into the Olympic pipeline, so we could be the first in California to do that as well. We’re ready,” Wang said. As a resident of Santa Monica, Wang said he and his family would be comfortable drinking the treated water from the new facility.

“I live in the city; I drink this water,” Wang said. “It would be really cool to make this happen and drink this water. It’s very rare that an engineer can actually say they designed the plant they drink the water from every day, and I’m very proud of that. So, if you were to ask us, ‘Is it safe?’ Well, I’d drink it. My son drinks it. My wife drinks it. So, hopefully, that would be some level of comfort for you.”

The project’s total cost is estimated at $95.9 million, of which a little more than $20 million comes from grants including Prop 1, LA County Measure W stormwater grants and state revolving funds green infrastructure grants. Another $20 million comes from city cash, specifically Measure V Clean Beaches and Oceans Parcel Tax fund and the local City Wastewater Fund. The remaining $55.6 million comes out of a City loan.

The costly project’s benefits include moving Santa Monica toward water self-sufficiency, but will not trickle down to lessening water bills, Wang said. However, it puts those rates into the hands of the City of Santa Monica.

Whereas imported water rates were expected to rise from five to seven percent in the near future, Wang said SWIP could keep that rise down to three to four percent, at least on the water production side.

“There’s a lot of other factors that go into rates that we have to look at: materials, manpower, equipment, like our vehicles,” Wang said. “About 65 percent of our operation cost is fixed, meaning whether you use one gallon or 1,000 gallons, we still have to expend that 65 percent of the cost on staff to operate the facility, having a standby fleet of vehicles, conduct repairs, maintenance, all of that staff time — that’s all fixed.”

The costly project would not result in rate increases, Wang said; it had already been worked into the budget and was paid for by other means.

But there’s one key question that remains: With all that sewage flowing in, will the Santa Monica Civic Center parking lot start smelling stinky?

No, Wang said.

Two large pipes collect odor that accumulates in the below-ground treatment facility, “scrub it clean” through filtration and release it via the planters next to the parking lot.

“When that air releases out, there should not be any odors,” Wang said, adding that the plant would “be a good neighbor.”

emily@smdp.com