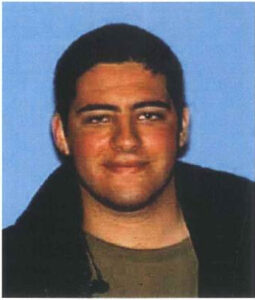

Twenty years ago, John Zawahri was my preschool student — a timid and quiet little boy. On June 7, he went on a shooting rampage in Santa Monica and killed five people before police gunned him down. Since this tragedy, I have been ruminating over what I could have done differently to help John when he was in my early education class.

I saw then that he had a difficult home life, and I worked with his troubled family as much as I could, however, my tool kit as an early childhood special educator was not equipped to handle John's serious family challenges.

Twenty years ago, we did not know what we have since learned from brain research about the effects of early exposure to toxic stress on a child's development. To effectively help John, we needed mental health or social work professionals working steadily to assist his family in developing productive ways to resolve the conflict that pervaded their lives. Today, more than ever, we need policy makers to put new knowledge into practice and support efforts to include the health of families as part of the education plan for all children. We must create a comprehensive system of care for our nation's most precious commodity — our future human capital.

Four-year-old John needed an early education program that could effectively address the chaos in his family's life. When John's mother contacted our school claiming her husband threatened her and her sons with a knife, we referred her to a local battered women's shelter where she found refuge and assistance. But with no mental health personnel on staff and no coordination with this outside agency, our early education program was ill-equipped to meet John's foundational needs and ensure his healthy development. John was a young child living amongst family violence, and his brain was formed under toxic stress.

"Toxic stress in the early years — for example, from severe poverty; serious parental mental health impairment, such as maternal depression; child maltreatment; and family violence — can damage developing brain architecture and lead to problems in learning and behavior as well as to increased susceptibility to physical and mental illness," writes Dr. Jack Shonkoff, the founding director of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University and prolific writer about the effects of toxic stress. "As with other environmental hazards, treating the consequences of toxic stress is less effective than addressing the conditions that cause it. … Brain plasticity and the ability to change behavior decrease over time. Consequently, getting it right early is less costly to society and to individuals than trying to fix it later."

Tragically, what ensued in John's case were subsequent years of family violence. His school programs were not able to effectively address the root cause of his developmental dysfunction.

Despite advances in brain science and toxic stress, there remains a chasm between research and practice. Dwindling economic resources have dictated drastic budget cuts to quality childcare programs, early intervention, school districts, social work, and public and mental health programs. Due to diminished funding, these programs have suffered cuts in personnel, fewer opportunities for collaboration, and little to no professional development. Well-intended programs remain in silos, so service coordination is rare. Continual program cuts have so eroded service delivery that the remaining programming is so inadequate it's wasteful. Research recommends systemic reform, yet dwindling fiscal support, bureaucracy, continued ignorance on the part of legislators regarding the direct correlation between healthy adults and the educational system prevails.

Education of the adults in children's lives must be an integral part of our nation's educational system. With a realistic view of the fiscal resources that are available, a rigorous inspection and reorganization of our health, education and social service systems is imperative. Community resources must be strategically embedded into our educational programs. Children do not develop in a vacuum; they are part of a family system that must not be ignored. If we do not invest now in children with unmet social-emotional needs, they will cost us much more later, as they become adults requiring mental health services, welfare assistance, medical care, or the resources of the criminal justice system. Clearly, a sound investment in early care and education with an emphasis on services that support healthy families is foundational to social and economic progress.

Fifteen years ago, I left my work in early intervention and joined the faculty at Santa Monica College. As an early childhood education professor I am dedicated to the development of a strong early care and education workforce. I have been privileged to teach and mentor many aspiring early childhood educators, who are filled with genuine passion for the welfare of children and families. But their passion, sound training and preparation are not enough. They must be part of an educational system complete with resources to meet the needs of children and their families.

We need to look at what we currently offer, revamp what needs revamping, and create a more cohesive coordination throughout our educational system to provide services for the caregivers of the children we serve. Researchers strongly recommend that in order to improve child outcomes, we must focus on building the capacities of adults that care for them. Without that, we will continue to observe the results of toxic stress and a generation of children whom we have failed. The safety and well-being of our nation is at stake.

Wendy Parise is a Santa Monica College professor in the Early Childhood/Education Department. She can be reached at parise_wendy@smc.edu