The son of a milkman, Robert Redford grew up in the 1950s in Santa Monica in the shadow of the movie studios. Rebellious in his youth, he had two sports heroes: Ted Williams and Pancho Gonzalez. (Neither exactly a “people pleaser.”)

Redford was 16 when he actually met Pancho. He was a ball boy at the L.A. Open when Gonzalez asked if he’d warm him up. Redford was eager to impress his hero with “winners.” But after five minutes Gonzalez snarled, “Hey, kid, just hit me the balls, OK?”

Interestingly, Redford still considers that day as among the finest in his life — “He just got to me.” This past Wednesday, May 9, would have been Gonzalez’ 84th birthday.

Last July, I was writing about the 2011 version of the same tournament (now Farmers Classic at UCLA) but I was struggling to find an angle. I searched the Internet and made two startling discoveries.

One, I hadn’t realized the event began as far back as 1927. (“Big Bill” Tilden won the first championship.) And two, that Pancho Gonzalez won the title in 1949 and then again in 1971. Twenty-two years apart? It had to be a typo. It wasn’t.

In 1971 Pancho was 43 while Jimmy Connors was 19. And yet, shockingly, Gonzalez won the championship 3-6, 6-3, 6-3. But how? Surfing the net (no pun intended), I came upon a YouTube video, a trailer to an award-winning documentary called “Pancho Gonzalez: Warrior of the Court.”

People criticize spending hours on the computer, but the next day not only did I have the documentary, but it was delivered by the director and co-executive producer, Danny Haro. In fact, we watched it in my living room! (Now if only Scorsese would do that.)

And so began my fascination with Richard Alonso (Pancho) Gonzalez. Born in Los Angeles in 1928 to immigrant parents Manuel, a house painter, and Carmen, a seamstress, Gonzalez grew up in the shadow of the L.A. Memorial Coliseum.

When Richard was 12, Carmen bought him a 51-cent racket at May Co. for Christmas. She hoped tennis would be an outlet for her boy who was drawn to speed, danger and adrenaline.

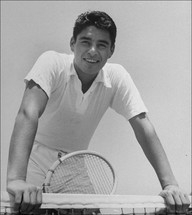

Reluctantly at first (he had hoped for a Schwinn bike), Richard took to tennis. But, whereas other kids had lessons at private clubs, he was self-taught, practicing endlessly on the public courts near the Coliseum.

Remarkably, eight years later Gonzalez won the first of his consecutive U.S. Championships. But the lily white sport was not exactly thrilled with a Latino champion. The “Jackie Robinson of tennis,” Gonzalez took the game from behind country club walls and onto the streets.

But, as opposed to Jackie, the 6-foot, 3-inch movie-star handsome Gonzalez had a fiery temper. During the 1950s and his eight years as the world’s top-ranked player (still a record), Gonzalez revolutionized the game with his huge serve, graceful footwork and fearlessness. His competitive fury made him controversial, but drew fans.

But Gonzalez’ was more than a sports story, it was an epic American tale. In 1918, his grandfather and father walked barefoot across 500 hundred miles of Sonoran desert to the U.S. fleeing the bloody revolution that killed much of their family. (Perhaps that explains Pancho’s fearlessness.)

Pancho’s life embodied the ‘50s American dream, which masked race and class discrimination. For example, Pancho would never have been permitted as a member at many clubs where he won tournaments.

At 21, with a wife, baby and another on the way, Pancho turned pro. (A decision that would later haunt him.) Banned from the glamorous amateur Grand Slams, Pancho was 40 when “Open Tennis” finally arrived in 1968. Otherwise, it’s likely he, not Roger Federer, would hold the record for the most Slam titles.

In 2011, Gonzalez was finally inducted into the prestigious U.S. Open Court of Champions. Almost 60 years after meeting Pancho, Redford asked to a part of the ceremony. (I also learned he’d be interested in seeing a screenplay about Gonzalez.)

Fascinated with Pancho’s tumultuous life, which included tennis glory and controversy, drag racing (his love of speed) and his love of women (six marriages), I spent three months writing “Fury and Grace” (which sits in Redford’s Santa Monica office where I’d like to think it’s aging like a fine wine).

But, more importantly, Wednesday was Pancho’s 84th birthday. Were he alive, I bet he’d still be playing tennis. And were he playing, I bet he’d still be winning. You see, Gonzalez “got to me,” too. Happy birthday, Pancho.

JACK can be reached at jnsmdp@aol.com.