PUBLIC SAFETY FACILITY — Det. Larry Nichols doesn’t have the luxury of calling for backup.

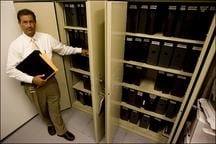

As the lone investigator assigned to the Santa Monica Police Department’s Cold Case Unit-Homicide, it is Nichols’ sole responsibility to solve the 66 cases that fill a large, fire-proof filing cabinet located on the second floor of the Public Safety Facility.

While the challenge may seem daunting to some, Nichols, a 19-year-veteran who began his career in law enforcement as a patrol officer with the LAPD, enjoys the opportunity to bring closure to the families of the victims. And not being on-call, leaving him more time to spend with his wife and son, doesn’t hurt either.

“It’s not the long hours so much anymore, it’s that this is a very tedious job,” Nichols, 49, said during an interview Thursday about the challenges that come with heading a unit that didn’t exist until two years ago. “I mean you are literally looking for a needle in a haystack. Not all crimes are solved right in front of your face. They really do take a lot of leg work.”

The Cold Case Unit, which also includes a detective dedicated solely to sex crimes, was created in September 2007 after former Capt. Jacqueline Seabrooks, now chief of police for Inglewood, conducted a feasibility study to determine if creating the unit was even a possibility given staffing levels. There are five homicide detectives dedicated to robbery/homicide.

Seabrooks, who was serving as the commanding officer in charge of the Office of Criminal Investigations, was approached by a detective under her command who asked if having a cold case unit was possible, prompting the study.

“And what a great suggestion it was,” said Seabrooks, who left the SMPD to join Inglewood before the Cold Case Unit was established. “I must admit that I was pleased to later learn that Chief [Tim] Jackman approved the establishment of the program.”

Seabrooks has created a Cold Case Unit at the Inglewood Police Department, “the basis for doing so is to ensure a community, and certainly the loved ones of homicide victims, that the police do not ever stop looking to resolve these cases.

“And more to the point, all things being equal, where there is a need, it is simply the right thing to do.”

When Jackman joined the SMPD he said there were a few cases that “bothered” him, including the murder of a German tourist in 1998 that at that point had not been solved (in February authorities arrested Paul Carpenter in Kingston, Jamaica for the murder). This led Jackman and his staff to do a comprehensive review of unsolved cases, and it became clear that there were at least 250 cases in which DNA evidence had not been analyzed. With new DNA technology available, Jackman felt it was imperative to dedicate more resources to clearing these cases.

He assigned Nichols to the homicide section and Det. Karen Thompson, whom he calls a “bloodhound,” to the sex crimes unit.

“These are crimes that I call life-time crimes because they impact the victims or their families in a way that no other crime does,” Jackman said. “These crimes linger with people and can be very psychologically devastating. These are crimes that people never forget.

“So in many ways these are the most serious crimes and it made sense to devote extra resources to it. I’ve got very extraordinary detectives doing phenomenal jobs.”

The formation of the unit came just as Nichols was looking to make a change. The long hours working homicide were wearing on him. He wanted something more stable. With the Cold Case Unit, he has set hours for the most part and is still able to do what he loves most.

“When you work patrol, you arrest people and write the report and that’s it, you’re done,” Nichols said. “After a while you get to thinking about what happens after that. What’s the next step? That was basically what drove me to want to be a detective, to be able to see a case all the way through to the prosecution.

“There’s nothing like getting a guilty verdict and have the family of the deceased sitting behind you in court,” Nichols added. “It’s the best feeling in the world.”

Off the ground

<p>

Getting the unit up and running was a challenge. Various detectives had different ways of organizing their files, leaving Nichols with a mess to sort out. He devised a system which he believes can hold up long after he’s gone.

Once he finished organizing the files, Nichols dove right in, analyzing each of the 66 cases, finding out which ones had more evidence than others and therefore would be easier to solve.

“After talking with my colleagues in the LAPD, they told me to start with the most recent cases first because chances are you will have an easier time finding people,” he said. “The older a case is the more difficult it is to find people.”

Nichols starts from the front page and works his way back, watching old interviews on video, conducting Internet searches to locate witnesses who may have moved. From there he starts knocking on doors, sometimes driving to San Diego or Northern California to prisons for interviews. When his work calls for him to visit more dangerous locales, he usually brings a fellow detective with him.

“Oh yeah, it’s time consuming,” he said. “You have to look at the evidence you have and determine how much you can realistically get out of each case. You have to prioritize. … I have several cases in the hopper right now.”

The cases date as far back as 1970. The most recent is from 2004.

A cold case is defined as any homicide that is five years old or older. There is no statute of limitations for homicide in California.

Technological breakthroughs

<p>

While some cases may have proved difficult to solve decades ago, new technology, including DNA analysis, has helped lead to convictions, Nichols said. Three cases have been cleared because of DNA technology and just recently Nichols received some good news regarding bullet casings recovered from a gang homicide at Eddie’s Liquor in 1998.

Nichols heard of a forensic scientist at the University of Leicester in Britain named Dr. John Bond who helped develop a breakthrough in crime detection — applying an electric charge to a metal such as a gun or bullet, which has been coated in fine conducting powder, similar to that used in photo copiers. When the charge is applied, the powder displays a residual fingerprint, even on casings that have been exposed to heat. It was previously believed that heat generated by gunfire would destroy any fingerprints. Quite the opposite. The heat actually helps the process by essentially burning the print onto the casing.

“The technique works on everything from bullet casings to machine guns,” Bond said in an interview with insideengineer.com. “Even if heat vaporizes normal clues, police will be able to prove who handled the gun.”

Nichols sent casings to Bond, who was able to lift a partial print.

“Now if we do have somebody who we are looking at, we can do a comparison,” Nichols said. “Unfortunately we have only a partial print and do not have enough points to put it into the system and get a match, but it could help us in the future. … It’s just another piece of this big puzzle I have to solve.”

While television shows make the processing of DNA evidence look simple, with results coming in before the commercial break, it isn’t that way in real life. Since the SMPD does not have its own lab to analyze DNA, samples must be sent out, and that can mean delays in processing. Nichols said it isn’t uncommon to wait at least three weeks to get samples back.

“It’s very important,” Nichols said of DNA evidence. “But it’s not the end all. There is still a lot of work that needs to be done.”