SMMUSD HDQTRS — Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District officials unveiled a plan last week to tackle the achievement gap between minority students and their white and Asian counterparts, proposing not just a change in instruction, but in district culture.

The proposal tackles the problem from multiple fronts that target not only material and methods of teaching, but also attempt to foster a sense of belonging and acceptance in the school setting.

In a time of reduced resources, that will also require that the district put other initiatives on the backburner as it pushes forward with its goals to even up achievement between students, said Terry Deloria, assistant superintendent of educational services.

"We may have to say that we'll put [a new initiative] in the parking lot because right now, we're focusing on the achievement gap," Deloria said.

The problem is simple to state, but historically difficult to solve.

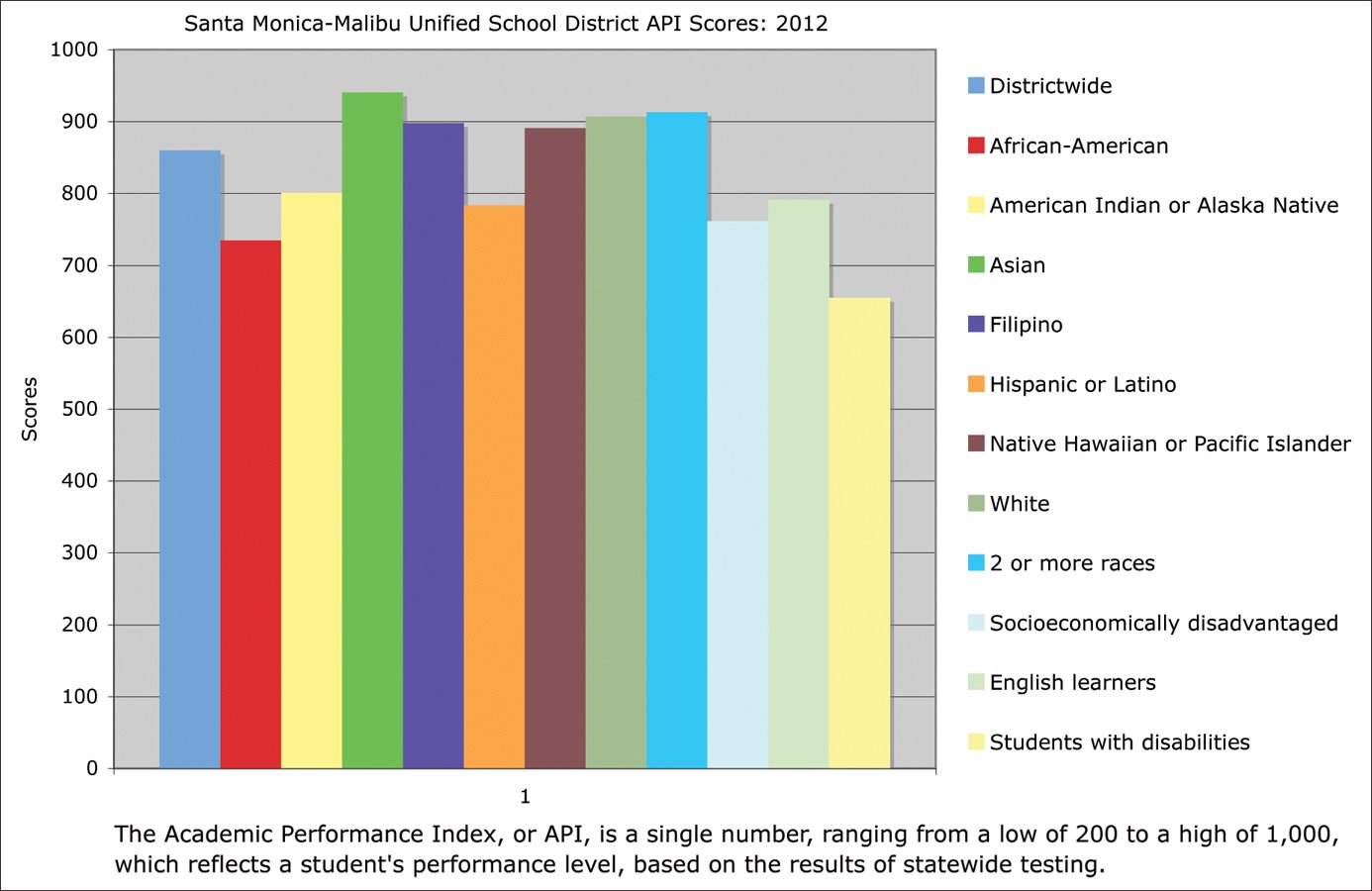

In general, minority students, English language learners and low-income students lag behind other groups in terms of performance measured by standardized tests.

One national measure, called the Academic Performance Index, shows African-American students trailing Asian students by almost 200 points in the SMMUSD in 2012.

Approximately 6 percent of African-American males in SMMUSD high schools are considered proficient in mathematics, a statistic that became a talking point in the November Board of Education election.

Attendance and dropout rates are also impacted by socio-economic status, according to the U.S. Department of Education, and a report by the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that children below the poverty level that read below grade level by the third grade are three times as likely not to graduate from high school as students from wealthier families.

Research shows that failure in high school has a significant negative impact on a young person's future.

Children who do not finish high school or get some kind of post-high school education are at greater risk of poverty, crime, incarceration, drug and alcohol abuse, domestic violence, shorter lifespan and poor health.

It's today's civil rights issue, Deloria said.

"When we fail our children, this is the kind of future we doom them to," she said.

To address it, Deloria proposes tackling the problem from four directions: teaching methods, district policy, culture and mentoring and advocacy.

Addressing failures in teaching and policy are two of the more straightforward tasks.

Leadership teams within the school will create five-year plans complete with baseline scores and measurable benchmarks in academics, college readiness, attendance, discipline and other metrics to narrow the gap.

Schools will also need to find ways to encourage minority students to sign up for advanced placement classes, and find teaching methods that fit individual student needs rather than approaching a class with cookie-cutter tools.

"There needs to be a systematic way that schools can look at every student and make sure they are doing well," Deloria said.

Culture, mentoring and advocacy are intangibles and consequently harder to measure.

In the wake of a racial incident in a Santa Monica High School locker room that created waves in the community in 2011, members of the school community requested that the district engage with Village Nation, a program that teaches adults on campus to be mentors to African-American youth and presents culturally-relevant assemblies three times a year.

Officials committed $10,000 to the program, but the full cost is four times that. Mainly African-American parents within the district have attended nearly every Board of Education meeting since to advocate for full funding for the program.

Fluke Fluker, a Village Nation co-founder, came last week to speak in favor of his program, which he feels could be the missing link to build a connection between Samohi and its African-American students.

Village Nation succeeds by focusing on culture over numerical scores, and by engaging the students on their own level, he said.

"Our goal is not high test scores, it's to make better choices," Fluker said. "When they make better choices, the byproduct is that they value their future."

Village Nation has already begun working with teachers at Samohi that are committed to becoming "elders" or mentors in the program. When asked if it mattered if the elders were also African-American, Fluker said no.

"These kids are more interested in you having soulful heart than you having soulful skin," he said.

Parents who oppose the program are afraid board members will be throwing money at an unproven method lacking in measurable results at a time when the district can least afford it.

"We focus on things that are wonderful without focusing on what works," said Lisa Balfus, the president of the Parent Teacher Association at Samohi.

Supporters, on the other hand, tout the relationship-building qualities of Village Nation, which go beyond numbers.

Boardmember Oscar de la Torre, himself the head of an organization that targets at-risk minority youth, said that he recognized the need for measurable outcomes, and cautioned Village Nation representatives that the board would need to see outcomes to get behind the program.

"Village Nation is a step in the right direction, and I want to express my support for the methods, but I agree that we need accountability, to set clear expectations and that the investment is well taken care of," de la Torre said.

Board members directed officials to take a look at the program and see if it could be integrated into Samohi's existing programs.

ashley@www.smdp.com