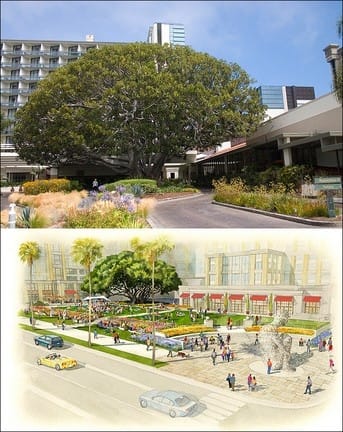

CITY HALL — Negotiations between City Hall and developers of a Downtown hotel will begin after the City Council voted to move ahead with the project in the wee hours of Wednesday morning despite widespread concerns about its design and imposing size.

The proposed revitalization of the Fairmont Miramar Hotel & Bungalows would double the size of the hotel to 556,000 square feet with between 265 and 280 hotel rooms, up to 120 luxury condominiums and almost 45,500 square feet of food, meeting, retail and spa space.

Councilmember Kevin McKeown, the single “no vote” on the dais, felt that the developer, Ocean Avenue LLC., which is owned by Michael Dell of Dell computers, was trying to fit too much on one site, and had effectively ignored direction given in previous meetings by not bringing a smaller project on Tuesday.

“It’s clear to me you’re trying to put 10 pounds of stuff into a 5-pound bag,” McKeown told Alan Epstein, a representative of the developer, Tuesday night.

McKeown tried to push planners to bring back an alternative design removing 25 percent of the square footage as a test, but the rest of Santa Monica’s council members did not get on board after Planning Director David Martin told them that a reduced project would be studied as a part of the environmental analysis.

McKeown’s comments were largely in line with complaints from both the Planning Commission, which had strenuous objections to the size of the hotel, and community members both for and against the project.

Over 80 speakers lined up for public comment, and while it was split evenly between proponents and opponents, even those in favor of the hotel had reservations about the look of the project.

Most proponents backed the project on the premise that the design would improve naturally as it continued through the rest of the municipal process, but that delaying the tax revenues and other benefits was not an option.

“I support the project, but this thing doesn’t have any style and grace,” said Robert Boucher, a retired engineer. “It has all the style and grace of a yellow cat.”

Gerda Newbold, chair of the Planning Commission, was less kind, calling the building monolithic, visually uninteresting, and out of scale with the surrounding neighborhood and uses.

“The project is not where it needs to be,” Newbold said. “We ask that you hold the developer to a higher standard of urban planning and design.”

In February, planning commissioners pushed for a reduced building, potentially eliminating all of the luxury condominiums that cap the proposed project.

Taking out the condos would kill the project outright, Epstein told the City Council.

Dell’s company, MSD Capital, bought the hotel in 2006 for $204 million and have since put in another $8 million to $10 million in improvements, Epstein said.

The proposed revisions would cost another $255 million, bringing the total to $469 million.

Without the luxury condominiums, which promise ready cash for the developer, that’s $469 million spread out over a maximum of 280 hotel rooms.

“The numbers don’t make any sense,” Epstein said.

Rather than reduce the size of the project, planners offered four other alternative designs for the building that kept the half-million square footage and spread it out differently.

The designs either involved a taller project with more greenery and open space or a shorter project with less. None reduced the overall size of development on the site.

The fourth option got the most attention by council members and the public.

It attempted to lighten up the design by axing an 11-story central bridge to create an open side on Second Street, a residential area that residents say would be severely impacted by the original design.

At the same time, there would be a three-story reduction in height at the corner of Second Street and Wilshire Boulevard that would then be balanced by a three-story increase to the “Ocean Building,” bringing it up to 14 stories.

That wasn’t enough for opponents, denoted by big red stickers that said “Stop!,” who maintained that the project was too big and decried the potential for increased traffic and loss of ocean views to properties in the area.

Although the council did move the project forward, nothing about it is legally set in stone.

The meeting was a float-up, a kind of trial balloon developers toss up to see if the City Council is on board with their concept before investing more money in design, architecture and the required environmental reviews.

The vote means that city planners and the developer can begin wrangling over the specifics of the project like the architecture and benefits City Hall can expect in return for permission to build taller and more dense than the city’s newly-adopted General Plan permits.

McKeown argued that the council had shot itself in the foot by approving the project’s preliminary concept with no formal request to consider a smaller design, ensuring that the applicant would not consider the reduced alternative.

“We should not have set the starting point so high that the design challenges are impossible to meet,” he told his colleagues after the vote.

ashley@www.smdp.com