It’s well-known among Santa Monica politicians and community members that homelessness remains a major problem in the city. Local leaders have identified it as a priority issue. Residents see it on a daily basis. So do tourists.

The annual count this past January tallied 728 homeless people in Santa Monica, more than half of which were living on the street. But their backgrounds and problems vary greatly.

“Homeless people are not a homogenous group,” said OPCC executive director John Maceri, whose organization provides housing and other services to homeless people in the area. “Homeless people as diverse as all the rest of us.”

The Daily Press spoke with Maceri about homelessness and efforts to address the issue locally. What follows is the first of two parts of the interview, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Daily Press: What trends has OPCC seen in homelessness this year?

John Maceri: We always see a spike in the summertime. When the weather’s warmer, people are moving around more, people are coming to the beach, and we see more movement up and down the coast between Malibu and the Palisades and Santa Monica and Venice. That’s fairly consistent. It’ll be interesting, as the weather gets cooler, to see if patterns are changing.

We all want to see the numbers going down. Santa Monica has done an extraordinary job in being able to maintain a level, whereas you see significant spikes [in other parts of the region]. That’s thanks to the groundwork that’s been done over the last many years with the police and fire departments. There was concern [about a possible spike in homelessness] when the Expo Line project was finished, but we haven’t seen that at our access center. I don’t think that’s proven to be true.

DP: To what extent does OPCC collaborate with police and other first responders?

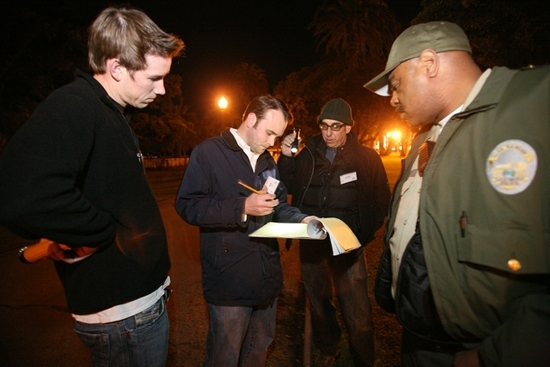

JM: We work a lot with the [police department’s Homeless Liaison Program] team. The HLP officers are at our Access Center [on Olympic Boulevard] several times a week, working with individuals they’re encountering on the streets and helping to connect them with services. We also work with the HLP team if they encounter homeless people who need services; our teams will go out and convene. We’ve had that relationship for a long time.

We work with the Santa Monica Fire Department as it pertains to homeless people who are in interim housing programs. Our nurse and the fire nurse have developed protocols for when we need to call paramedics for medical emergencies. There are times that’s not necessary, and we’ve done training for our non-medical staff on what constitutes an actual emergency where 911 needs to be called. We work with chronically homeless folks, so we see a lot of heart disease, hypertension and diabetes, and there are times when we need first-responder assistance.

We try to be very sensitive to the fact that first responders are busy, and that’s an expensive intervention that should only be used when necessary.

DP: How does OPCC get homeless people off the street and into housing?

JM: It usually starts with something as simple as access to restrooms and showers. The ultimate goal is to move people into permanent housing. We have an on-site medical clinic with primary healthcare, mental health services, domestic violence counseling, substance abuse treatment and referrals. It’s a range of services. Sometimes it’s making people aware of what’s available to them. It’s building a relationship with them and getting them to understand what’s available.

DP: What about the homeless people who don’t want services or don’t trust the agencies providing them?

JM: Building trust takes a long time. There are a lot of homeless people who are struggling with mental illness or addiction, or they’ve been in and out of the system in foster care or jail, or they’ve been in and out of treatment. They may not have been on medication for a long time, so it’s hard for people to make rational decisions. A lot of our work is about building that trust and finding people in a moment of clarity. There is a lot of mistrust. They’ve been disappointed if they’ve been in and out of the system. It’s hard to get them to trust that something’s going to be different.

You can’t physically force someone into treatment. Our ability to serve people is based on our ability to persuade them. “Yesterday you weren’t quite ready, but how about today?” It usually happens when health deteriorates, where you get tired of being tired, or after a bad episode where they feel threatened. That’s when we can intervene. We don’t give up. We do whatever it takes for as long as it takes, but that can be a very long time.