OCEAN PARK — Debbie Bernstein doesn't freak out when neighbors, or even strangers, stop by her Ocean Park home and make off with a book left out in her front yard.

After all, you can't steal it if it's free.

The former high school English teacher is one of thousands in the United States and across the world participating in the Little Free Library network, an idea that's achieved almost social movement status amongst its devotees who forge community ties through sharing the written word.

Each Little Free Library volunteer sets up a box-like structure — either homemade or from a kit provided by the nonprofit for a fee — and fills it with books available to all who pass by. In return, those who take books are expected to drop off another, possibly with a note to future readers, and continue the connection.

Co-founders Todd Bol and Rick Brooks established the first library in 2009. Since, over 6,000 have sprung up throughout the Midwest, both coasts and tens of other countries.

Maybe that's what happens when you pair two entrepreneurs with decades of international and domestic nonprofit experience between them — a simple concept meant to encourage literacy and connect neighbors becomes an online phenomenon.

"We're both idea guys," Brooks said. "We thought it could carry a lot of different freight and accomplish a lot of different things."

The project began as a personal one, and has only become more so as it spreads.

Bol built the first library in memory of his mother, June Bol, a teacher and generous spirit.

"She was one of those rare people you meet and you think, ‘I feel better about myself after spending time and talking to them,'" Bol said. "There's something magical about them. They ask how you are, and they really mean it."

June Bol would have literally given the shirt off her back, Bol said, and he felt there was no better way to honor her memory than to create the system which evolved into Little Free Library, where books are freely given and the generosity is rewarded in kind.

The first one went up in Bol's front yard, and caught the attention of his neighbors. He put up another on a busy bike path that saw 20,000 to 30,000 passersby each day.

"It grew pretty quickly after that," Brooks said.

Getting started with the Little Free Library is as easy as going to the organization's website and ordering a $35 kit that comes with a numbered sign identifying it as an official library and information for the new "steward" on how to make the project a success.

Register with the organization and your library shows up on a Google map on the website populated by thousands of icons giving the location of the library for those in search of a book.

The website also provides patterns for those who want to take library construction into their own hands.

Disparate ends of society got involved in the project, from prisons to high schools.

Walmart requested one for its flagship store, and activist filmmaker Michael Moore also chipped in, said Bol.

"To encompass Michael Moore and Walmart in the same thing is pretty magic in itself," Bol said.

Each of the free libraries — first called "habitats for humanity" as a nod to the nonprofit that builds homes for the needy — takes on the feel of the neighborhood in which it is situated.

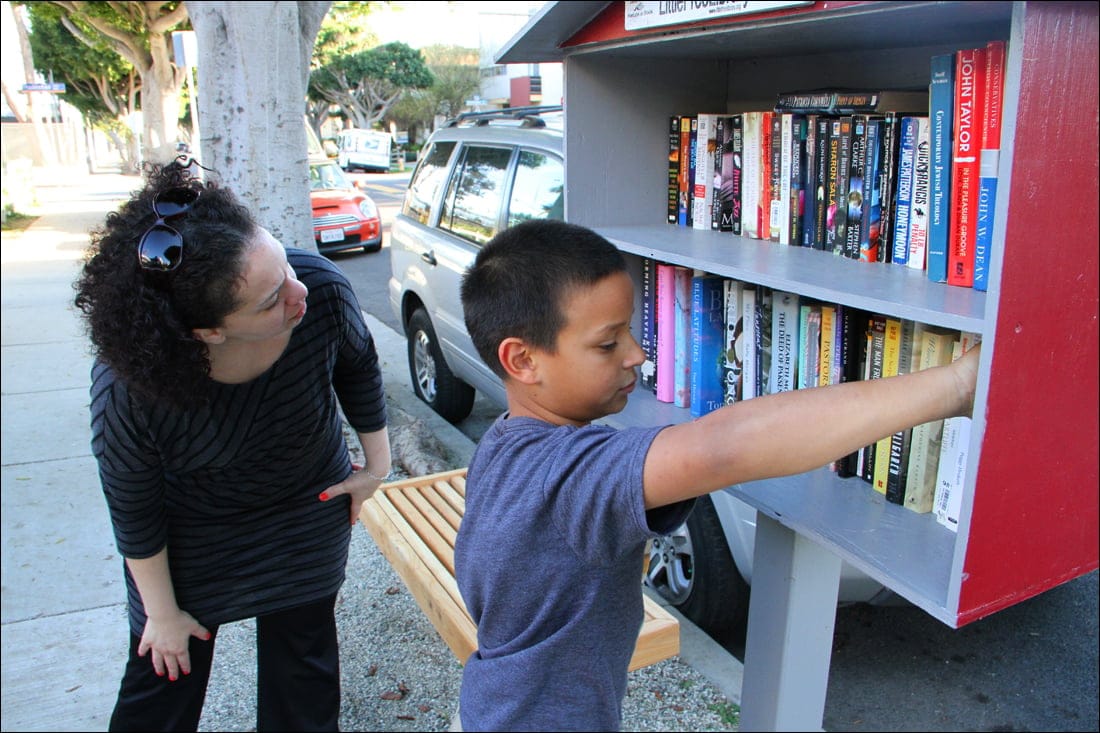

Bernstein's husband Nick Johnson, a current English teacher, built their Little Free Library #3904 from scratch, and Bernstein stocked the shelves with books she'd kept in storage before the family moved out of their rental and into their Ocean Park home two years ago.

They were inspired by a 2012 Los Angeles Times article on the subject, and saw an opportunity to share favorite books with their new community.

"I had saved books that I loved thinking I want these books, and when I went through them I realized I don't have to have them all," Bernstein said.

As neighbors began to realize what was going on, new books streamed in as quickly — or quicker — as old ones left. Soon, the library was taking on a life of its own.

Bernstein noticed that children's books disappeared in a flash, perhaps because of her proximity to John Muir Elementary School, and the books that repopulated the shelf had a decidedly feminine slant.

"It's evolved its own theme," Bernstein said.

Author Nora Roberts, mystery-thrillers, even non-fiction from politics to child-rearing have all made an appearance, she said.

Bernstein herself is more of a biographies fan, but the arrival of the new books has stretched her horizons, like Augusten Burroughs' "Running with Scissors" and Jeannette Walls' memoir "The Glass Castle."

The neighbors love it, Bernstein said, and she's gotten thank-you notes and phone calls. There's never been a problem keeping the library stocked.

Thievery and vandalism are two of the most common questions put to the Little Free Library founders.

Book-theft is easy, Brooks said.

"You can't steal a free book, so that problem's gone," Brooks said.

Vandalism has been extremely uncommon.

One steward thought their library had been burned by an arsonist, only to discover that it had been hit by lightning.

"The theme was that books are the keys to knowledge, and they had keys on the library that attracted the lightning," Brooks said.

Although Little Free Libraries are growing in popularity, Brooks and Bol are not done growing the idea.

They plan to launch a new website with improved maps, and are working with the American Association of Retired Persons, more commonly known as AARP, to do almost Meals on Wheels type outreach to reach out to homebound seniors.

"Keeping up has been quite a challenge," said Brooks, who has a full-time job. He's received three paychecks from Little Free Library LTD since it was founded.

"We want to set up a self-sustaining network. We've resisted commercializing, because that's not quite the idea. The idea is that people get involved themselves," Brooks said.

And they are.

It's a fitting tribute to June Bol, whose memory lives on in the Little Free Libraries, her son said.

"It's the energy and spirit of my mom and who she was," he said. "My mom dances everywhere."

ashley@www.smdp.com